Richard Andersen was frozen in place for what seemed an eternity.

Everyone at Candlestick Park in San Francisco for Major League Baseball’s World Series that day eventually realized they’d just experienced a major earthquake. But there was no information; no way to communicate.

It was 5:03 p.m., Oct. 17, 1989.

The San Francisco Giants were playing the Oakland Athletics for baseball’s championship and key executives from every team in baseball were in attendance. The general consensus was that Oakland had an unbeatable team, with Mark McGwire and all the other talent on hand.

It was pre-9/11, when security and emergency protocols changed dramatically in the venue world, but it had its own impact on future stadium construction and operation – and on every individual who was there.

“I was a young executive of the Pittsburgh Pirates. Carl Barger, the president of the team, had become my mentor; the dad I never had,” Andersen recalls. “Carl was a brilliant lawyer and strategist and one of the funniest human beings I’ve ever known in my life.”

They were joined by Jim Leyland, the manager of the Pirates at the time. “And Jim loved Carl. We’d all been together a couple of years.”

As VP of administration/operations, Andersen’s role included going to key events with the executive team and acting as the front person, “coordinating stuff.” He was just 34, very young to have a role like that. “It was incredibly cool,” Andersen says.

It was Game 3 of the Series, and Andersen clearly recalls going to the opening reception that Bob Lurie, owner of the Giants, threw. After the owner’s reception, they were walking back to their seats.

“We’re on the walkway between the box seats and the second tier, almost to home plate. I hear an airplane going over that really sounds loud. The reverberation is so loud, I look up. Suddenly it’s shaking. Then I look at the light tower above third base, it’s swaying 10 feet side to side, left to right. Holy shit.”

Andersen was standing with Barger and Leyland. He’d never been in an earthquake, but they all realized at the same time what this historic 6.9 magnitude quake was.

“I see chunks of concrete falling, small ones. It went on for what seemed like 45-55 seconds [actually it was 15 seconds, according to the history books]. There were thousands of tremors for the next few hours.

“I stood there paralyzed for 40 minutes. I didn’t know whether to go up or down. I didn’t want to be under the overhang. There were no announcements. Nothing on the video board.”

Cellphones were just out. It was not the age of the Internet.

Finally Andersen, Barger and Leyland slowly made their way down to their seats in the Commissioner’s Box with other owners. Word of mouth and visuals was all they had.

Rumors were spreading like wildfire, like that part of San Francisco had fallen into the Bay. The Golden Gate Bridge had fallen. There were massive casualties.

“We can see smoke rising on the horizon, but can’t see what’s going on.”

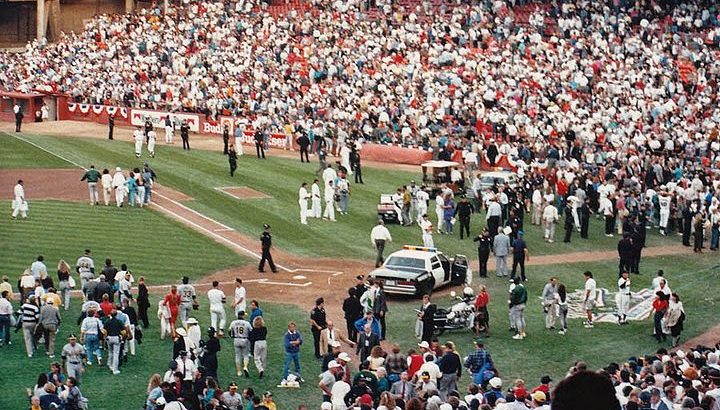

Every security person known to man was at the World Series Game. Suddenly what seemed like the entire SWAT team for San Francisco lined up and ran across the field and out the centerfield gate. Then the players left out the centerfield gate.

As a police car came to home plate, officials attempted to make an announcement so garbled you couldn’t understand it. They’re using a megaphone in a 70,000-seat stadium. There were no backup generators. If this had happened an hour later there would have been mass casualties, because there was no lighting in the stadium either. Everything was out.

“We sat there with no information.”

“Ultimately Jim, Carl and I made our way across the field. We had a limousine. We got to our car. After six futile hours of trying to get out of town and being unable, we had our driver take us back to the Park 55 in downtown San Francisco,” Andersen remembered.

“Carl is not a big guy, but he’s very confident. He’s also not a healthy guy. And he’s a chain smoker and pretty big-time drinker. I’m worried about him. His room is on the 26th floor. There are no elevators. I’m on the 11th floor. I’m in a small room with a twin bed. I convince Carl he can’t go up to the 26th floor.”

It was 4 o’clock in the morning now.

“Carl, let’s just go to my room; try to get some rest. We’ll have the limo driver pick us up in the morning now that we know the Golden Gate Bridge is open. We’re going to Lake Tahoe where I have a friend who runs the Hyatt and we’ll fly out of Reno and get home.”

So they had a plan. They get to the room, exhausted. Everywhere in the darkened room Andersen sees the little red glow of Barger’s cigarettes. He’s set them on a window sill or a dresser.

“Damn it, boss, quit smoking, put these out.”

Barger finally gets into his boxer shorts and keeps saying, “Can you believe this, can you f**king believe this?”

“It’s surreal. I don’t know how to describe a 6.9 earthquake, but it changed my life forever. You realize, you don’t control anything.”

Carl has been convinced to get some rest, so Andersen begins to get undressed. “All of a sudden, as I begin to pull my boxer shorts off, Carl sits up in bed, and shouts, ‘There’s no way you’re getting in bed like that.’”

“But Carl, I can’t sleep unless I’m naked.”

“There’s no way you’re getting into bed like that!”

Laughing, Andersen replies, “Of course not, I’m not getting into bed with you period.”

The next day, they took the 11-hour drive, which is normally about 5.5 hours, to Tahoe, seeing the massive destruction in the Marina District as they worked their way out of San Francisco, a 3.5 hour endeavor that day.

In tragedy like this, people have to take the edge off, and humor helps. It’s funny what you remember, like Leyland, admittedly tipsy as were all the inhabitants of the limo that day, saying he wished he could play golf that day. “Imagine how big those holes are. A hole in one on every hole.”

Or Leyland finally getting to a payphone to call his wife, Katy, knowing the last she knew of him, the screen went blank on Game 3.

“Did you get hold of her?”

“Yeah, it disturbed me. I said, ‘Hey Katy, it’s Jim.’ And she said, ‘Oh shit. I thought maybe you’d fallen in a hole out there.’”

Or Andersen joshing Barger that he was going to climb into bed with him naked.

Sitting in the limo with two chain smokers, Andersen thought back to the night before and how lucky they were. It was a major tragedy, with 67 people killed, 3,000 injured and $5 billion in damage, but it truly could have been worse. If it had happened after dark, people would have died at the ballpark.

Safety and security are at the top of the list for venue managers today, and it’s partly because of experiences like the one baseball’s elites experienced the day the World Series shook.

We should not forget that one day in history, people stood there in a major league baseball stadium and didn’t know what to do and there was no way to tell them.

It’s a big part of why we changed the way we do things. — Based on a true story as told to Linda Deckard