When some Eastern European promoter poured beer on the ticket stubs so they could not be accurately weighed, Stuart Ross found a workaround.

Concert production pro Ross didn’t know the scope of his problem when he found a solution.

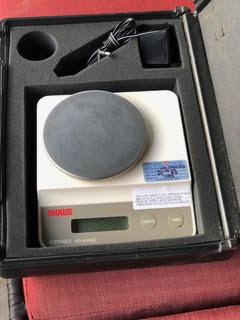

He discovered a scale that could weigh/count the hard tickets sold for Lollapalooza general admission at a Western Fairs Association trade show in 1992. The scale was being touted as a way for fair managers to weigh carnival ride tickets to determine their true percentage of income. It was just what he needed to check the ticket count at the touring festival for which he was tour director.

Rumor has it that that same “technology” Ross introduced to the touring alternative music festival was quickly adopted by the Eagles and the Rolling Stones as well.

In this day of computerized tickets and better accountability, a scale to weigh hard tickets seems archaic. In the 90s, it changed his world. And truth be known, though Ross has not employed the scale, which he keeps in his garage as a museum piece, in more than a decade, it still has its uses.

LESSON LEARNED: Don’t dismiss businesses that you think have old technology.

This all started because Ross is an avid and curious reader. Among his preferred publications was Amusement Business, the now defunct trade paper published by Billboard which tracked the mass entertainment business, defined as any live, ticketed event, from concerts to fairs to amusement parks to carnivals. He appreciated that Amusement Business reported per caps and ticket grosses, attendance and promotions across all genres of live.

In 1991, Ross was part of the team working with Perry Farrell, who had conceived a touring festival as Jane’s Addiction’s farewell tour.

After Ross hooked up with Farrell and had done the first year of Lollapalooza, which was 1991, the decision was made to turn it into an annual tour, scrapping the original Farewell Tour concept. But Perry Farrell wanted to continue to do a lot of things you don’t see. “We were going into amphitheaters – that’s the career arc. But he also said, ‘listen, let’s get seven opening acts and a bunch of alternative food and beverage, like huge burritos, and political booths. We’ll put the NRA next to PETA. Okay, let’s figure it out.’ So we started a company to produce Lollapalooza from that day forward.”

“I had seen in Amusement Business that there was a fairs convention in Palm Springs at the Palm Springs Convention Center.

“I find trade shows to be fascinating no matter what they’re about. So I’m walking around the Western Fairs Association show and there is a guy who is demonstrating a scale. It’s a scale to count the little roll ticket stubs for carnival rides. Imagine how long it would take to hand count those. He was demonstrating to everybody.”

“I put 30 tickets in and the scale says 30.”

“Oh my god, this is the greatest thing I’ve ever seen. Can it be used on any size ticket?”

“Sure it can, you just use the tare function.”

Ross immediately bought one.

To use it, he put a bin on the top (like a plastic shoe box), and then counted in a sample of 50 stubs. The scale allowed him to tare a quantity. Once it knows the weight of 50 stubs, the drop is weighed. “We could count about 30,000 tickets in a half hour or so. Accuracy is about four per thousand,” he said.

Two or three of the Lollapalooza staff would weigh the drop. The promoter was included, of course. One person would weigh, call out the number and dump the counted drop into separate bags, another would put the number into a spreadsheet, and the third person would continue to fill the bin. Kelly Weiss, who is now music business affairs at ICM, was the ticketing person on the Lollapalooza tour and was a key member of the stub-weighing team.

Before buying the scale, Ross was always second guessing accountability. Could he trust every promoter to give an honest count? In 1992, he had a way to check. “We started to grab the drop every night and weigh it, just like they do at fairs. We knew exactly whether the audit matched the drop, not to one ticket but if something’s way off, there’s something wrong. We did this every night and no one had ever seen it in our business.”

In Eastern Europe, there were a few promoters who decided to send people in and dump beers in the drop count bins outside, ostensibly to ruin the count, Ross remembers. “Unfortunately, it simply made the stubs weigh more, which would have increased the drop. In actuality, we weighed the wet stubs separately, and got an accurate count on those also.”

He recalled another night it paid off bigtime. “I was in Russia with Metallica and we were playing the stadium. I’m getting ready to settle.”

“How many tickets have we sold?”

“Here’s the box office audit.”

“Guys, that doesn’t seem right to me at all. Let’s figure this out. Do you have any paperwork from the printer?”

“No, we don’t have anything.”

Having already planned that this could happen, Ross had hired his own people to be at every gate and to protect the ticket drop, making sure no one took it. They grabbed all the drop and weighed it in front of the promoters and it was almost double what was reported.

“There aren’t that many people here.”

“Okay, show me where I’m wrong. If you want to weigh it, go ahead. I’ll just sit right here.”

And that’s how Ross got paid on a lot of shows where there was no back up but the drop count.

LESSONS LEARNED: Don’t dismiss businesses that you don’t think are relevant, because there are a lot of techniques and tricks and smart people that work in these industries. They did not build the scale either; they simply repurposed it.

In the concert touring industry, especially among below-the-line guys like tour accountants and tour managers, we share information. If we figure out there is a better way to do it, we don’t hide the fact.

Lollapalooza was a festival. Doors opened at noon and the show ended at 11 p.m. and then they packed everything up — people, equipment, food vendors — and went down the road for 7-8 hours, got to the next city, set up and did the same thing. They did close to 300 shows in seven years. That ticket scale was worth its tare in gold. — Based on a true story as told to Linda Deckard

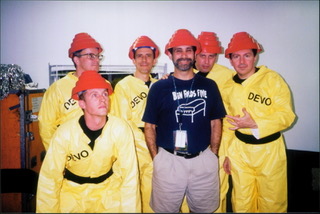

Photo: Top: Stuart Ross with Devo during the 90s at Lollapalooza. Below, the original ticket scale, which now resides in Ross’ garage. (Courtesy of Stuart Ross.)