Marilyn Manson’s opening act was Nashville Pussy. The show was set for April 28, 1999, at Five Seasons Center (now U.S. Cellular Center), Cedar Rapids, Iowa, a small and conservative town.

“When we announced the show, the biggest issue was that on the marquee we advertised Nashville Pussy as the opener. So I would say to those concerned people in town, that that means “cat” to me; I don’t know what that means to you,” said Tammy Koolbeck, who was the arena’s director of Marketing at the time.

“In retrospect, if that had been the worst thing that had happened, that would have been great. TV stations were showing the marquee with the name blurred out. The TV could talk about it but couldn’t show the actual name,” she recalled of the climate at the time.

But that’s not the worst thing that did happen. “It’s like the day you got married or the birth of your child. That’s how memorable it was,” Koolbeck says now.

On April 19, 10 days before the Cedar Rapids Marilyn Manson show, the shootings of and by schoolkids at Columbine happened. Today it’s a textbook scenario for safety and security training. At the time, it was unprecedented and unbelievable. Media reports were saying that the shooters listened to Marilyn Manson’s death metal music, one among their many inspirations.

“Overnight, things just changed for us,” Koolbeck said. “For that week leading up to the show, it was interesting.”

Then, Cedar Rapids found out it was going to be the last show on the tour. Manson was canceling the last five or six shows of his tour.

“In reality, we probably picked up 1,000 tickets in that last week. We had people flying in from Vegas for his last show. The show wasn’t really selling, it was kind of done, then Columbine happened, shows were canceled, and fans decided to come to Cedar Rapids to see it,” Koolbeck said.

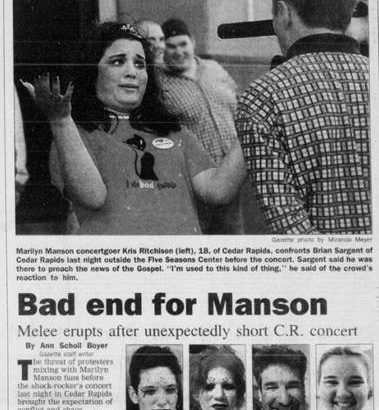

Things were heating up. A woman in Cedar Rapids started a petition to make the show go away and had gone to City Council. Five Seasons Arena was managed by Ogden Entertainment at the time. The mayor said, “We’ve hired Ogden to handle this and even though I don’t like his music and I wouldn’t send my kids to his show, it’s a First Amendment issue. We’re not going to stop people from protesting.”

So the arena staff began setting up protest areas and managing the deluge of calls. “We were getting lots of calls,” Koolbeck said. “Sharon Cummins, our executive director at the time, first started taking calls and it was soon decided we would just have one voice. It was easier to repeat the same thing over in the same words. I, as the Marketing director, was the spokesperson. It was not a new role for me. I’d been hired to do it.”

The Dyersville Methodist Church, probably 50 miles away, called to say they were praying for Tammy Koolbeck.

“We just wanted you to know the congregation is praying for you and your soul if you’re going to let this happen.”

“Thank you.”

“Are you really going to let them sacrifice puppies on stage?”

“There is no sacrificing of animals during this show.”

“He sings about killing police officers.”

“You should read his lyrics. It really talks about killing yourself, not killing other people.”

Koolbeck was taking 20 calls a day. The receptionist knew to forward all inquiries to Koolbeck. She did not take messages and offer a callback. If Koolbeck was on the phone, she’d suggest if you’d like to call later, you can.

“If they started cursing at me, I hung up. ‘I’m happy to answer your questions and hear your concerns, but you can’t call me names,’” Koolbeck said.

At Target Center in Minneapolis, the second to last show, they chose not to take the calls, Koolbeck remembered. “Everything was going to voicemail and they weren’t responding back. In Minneapolis, you can probably do that. In Cedar Rapids, you can’t.”

When she was talking to media, she had a script.

“Yes, the show is booked.”

“No one can hear or be exposed to the music unless they bought a ticket. The sound does not leak through the concrete of the building.”

“Security is in place.”

“This is where people can protest.”

“This is the time of the show.”

“This is a First Amendment issue.”

“I can’t tell you what happened in Columbine.”

The day shows up. Four or five satellite trucks have come in for the last show. It was a big deal.

The big protest area was on the other side of the street and the satellite truck blocked their view of the building. “That worked out well,” Koolbeck says.

It was a general admission show, so everybody came to the back of the building. People were led through a maze of fencing to get into the building, so the search went well. Back then, it was visual searches to find chains or knives or bottles.

“Everything was really going well. Marilyn Manson concertgoers were very respectful,” Koolbeck remembers.

Everybody gets in; the show starts; all good; and Marilyn is in encore. He usually sings two encore songs. It was a little after 10, she recalls, because she had done the final touch-base outside with media who went live at 10 p.m. The satellite trucks pulled out. Koolbeck went back into the building.

“Next thing I know, the encore song stops and the lights go up. He hadn’t sung ‘Beautiful People,’ the one song I wanted to hear. What is going on?”

Koolbeck’s hearing on the radio that they’re pushing people out, the show’s over.

Koolbeck was in the incident room. “By the time I stepped out, I heard the call to put up the house lights. He left the stage in the middle of a song; kicked over a drum set on the way out. I come back inside to do the debrief.”

“That’s when I found out a ‘Smiley Face’ had shown up on the drum set and when he saw it, he got mad and kicked the drum set over,” Koolbeck said. The next day, a church said they came in and put it up on the stage. “I’m sure we did bomb dogs; we cleared the building before soundcheck. There was no way anyone got onstage.”

After checking that it wasn’t an arena staff issue, they discovered one of Marilyn’s crew members thought it would be funny and put the Smiley Face up. He or she didn’t realize how mad he would be.

Koolbeck is back in her office, incident over, when she hears fans have surrounded the Marilyn Manson bus. “I go outside and, all of a sudden, police and squad cars are everywhere. Police are getting out in riot gear.

“What’s happening?

“I get around the corner and see there are people around the bus and they had started to rock it. It was just like you see in the movies. Police locked arms and down they went to disperse the crowd. They started cuffing people. There were no cellphones then, but someone had a video camera. The person dropped it as they started to run.”

Koolbeck and the police commander were moving toward the melee. “I don’t think it was more than five minutes. It was maybe over in three.”

Local media was still onsite. Koolbeck had just talked to the Des Moines Register reporter, giving him attendance numbers and how she thought the evening went. “We thought, ‘gosh, this went better than we thought.’”

Police ended up arresting 23 people.

“I remember coming back around the corner and one of the TV stations was interviewing the hotel security guard. I went immediately in and told Sharon to call the hotel GM and tell their security people to stop talking.”

Koolbeck was called back to do an interview with TV. First, she talked to the police commander. “After the interview, I thought I could have done that a little bit better.”

Ten minutes later, the TV station called to redo the interview because they didn’t “white page” her. Back in those days, they had to put a piece of white paper in front of the camera to reset the color to start the shot. “They’d ask your last name and how to spell it. This time, they didn’t do that so I looked like a Smurf, everything was purple. I got to redo the interview.

“I think I took out a bunch of ‘umms.’ I knew what they were looking for…how someone got on stage, what happened, why did the lights go up.”

“Something happened on stage. “

“The show was over.”

“He was in encore.”

“Marilyn decided the show was done. When we realized he wasn’t coming back on stage, we put the house lights on and asked people to leave the building. On any GA show, we clear the floor that way.”

Koolbeck would have been 33 years old at the time.

The main lesson learned, which she teaches in her media relations course at IAVM’s Venue Management School, is know what you’re going to say and continue to say it. It needs to be clear and concise. Don’t rush anything.

“Just because the TV people wanted to talk to me right then, I said I’m going to talk to the police commander first so I have more to share with you. Right now, I don’t have anything to share with you.”

“For us, in the community we were in, we handled it by talking to the people who wanted to be heard.”

“I still get a little choked up. For some, like the lady who petitioned City Council, this was very personal to her.” — Based on a true story as told to Linda Deckard

I know the person who was the venue runner for that show. One of her errands was to go buy the stuff for the smiley face sign – marker, poster board, etc. When she found out that was why Marilyn stopped the show she literally ate the receipt so there was no proof she was involved. 🙂