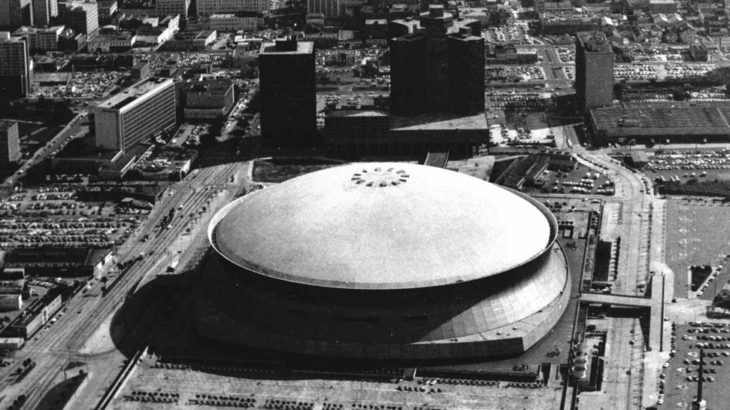

The Louisiana Superdome, New Orleans, circa 1975.

Legend has it that when Denzil Skinner privatized the Louisiana Superdome in New Orleans in 1977, he faced extreme dangers probably unknown to venue managers today. When David, Denzil’s son, and Mike Noah, his son-in-law, first toured the stadium, they opened every door, and found people’s living rooms behind several of them. Someone was turning the stadium into a hotel, a revenue stream the owners weren’t privy to.

But evicting the “tenants” was the least of their worries.

The parking lot was bleeding money. Having installed several counting systems, like the entrance arms that raise up at each car admission, only to have them consistently and instantly broken, Denzil sent David and Mike into the street to count cars the old-fashioned way. As they worked, all sorts of shit, probably literally, rained down on them, missiles from the upper levels.

The tires of their cars were slashed so frequently by ill-wishers, they started driving jalopies with cheap tires to work to keep the cost down.

It was armed-guard territory. It was brutal. It was corrupt. It was New Orleans in the 70s.

Denzil Skinner assumed a high level of professional and personal risk when he took on management of the Louisiana Superdome. Later, he and his partner A.N. Pritzker of Hyatt Hotels, decided they were good enough at this gig to expand to other venues, forming Facility Management Group, which was later merged with Spectacor Management Inc. to become Spectacor Management Group to become SMG to ultimately merge again with AEG Facilities to become, by the end of 2019, ASM Global.

That is Denzil’s legacy. Denzil Skinner died April 4, 2019, at his home in Williamsburg, Va., but his contributions to this industry will not be forgotten.

It all started with an idea in Denzil’s head that if only he wasn’t crippled by all the things you are encumbered by when running a municipal building, mainly bosses that don’t get it, and mayors and city councils that don’t understand the industry, this could be a business, recalled Tony Tavares, who worked for Denzil at one point and was later president of the merged companies that became SMG. “You’re forced into their methodology and purchasing habits. Denzil said, ‘if I can ever run this like a business and not be encumbered by the political volatility, I can really make a difference,’ and he did.”

Denzil had learned those lessons in 16 years of venue management, beginning in 1960, including gigs in Charleston, W. Va.; Norfolk, Va. and Indianapolis. In 1977 he joined with A. N. Pritzker of Chicago to negotiate a management agreement with the State of Louisiana for the complete control of the Louisiana Superdome.

Those who remember Denzil’s heyday in the business give credit to the man for being a pioneer and, if not the godfather, then darn close to it, of private management of multiple venues under one banner.

Based on Truth is all about stories, and Denzil’s is a great one.

Tony recalled that the Superdome was poorly managed and losing millions of the state’s dollars when Pritzker of Hyatt Hotels recruited Denzil to negotiate a management contract to take it over. That contract was based on a guaranteed reduction of debt for a fee and a commission based on, for example, 25 percent (the number is not verified) of any additional debt reduction beyond that guaranteed figure. It’s a formula that is still applied today, though in truth, every contract is different, just as every city is different, noted Cliff Wallace, who worked for Denzil at the Superdome in the early 80s.

Cliff recalls that A.N. was acting to protect his interests, the new Hyatt that had just opened adjacent to the Dome in New Orleans, when he agreed to manage the venue. At the grand opening ceremony at the Hyatt, the governor of Louisiana said to Pritzker, from the dais, “look at that building behind us. Would you manage that building for us?”

When A.N. said sure, he would, he had no idea the mess he was signing up to rectify. Denzil probably had a better idea how bad it was. At the time he was recruited by A.N., he was managing the new Market Square Arena in Indianapolis. Growth strategist David Petersen, who worked for Pritzker and did numerous studies for the International Association of Auditorium Managers (now IAVM) where he met Denzil, was probably the one who recommended Skinner to Pritzker. It is a relationship business.

Denzil recruited his son and son-in-law, and they headed South. They were the attack team, there to find out what they could do to change things around, where was it fat and where was it bleeding, Tony said.

The problems they encountered were not necessarily unique to public assembly facilities, just on a bigger scale. “If I thought we could make a bunch of money, I would do that. I might be in the minority of people sadistic enough to do that, but I did that on a lesser scale when we took over several buildings,” Tony said. “You figure out a way to come up with approximately how much you are losing, then put a sting operation in effect. We were able to catch several people who were stealing in my venues.”

Welcome to venue management, the less glamorous version.

Cliff was recruited to run the Superdome when Denzil, David and Mike were planning to move to corporate offices for Facility Management Group in Virginia. He originally met Denzil in Champaign, Ill., in 1973 where IAAM held executive management seminars for awhile. Cliff and Denzil were in the same second-year class. Cliff was in awe of GMs like Denzil, being a lowly assistant GM in Greenville, S.C., at the time.

Photo: First row: J.O. Weisenberg, Larry Strate, Harlo Thon, Al Leggett, James Cowen, Phil Quinn, John Pingel and Irwin Ellis. Second row: Bill Wilson, Bill Turner, Jimmy Gatlin, Joe Singletary, Ron Wigmore, Tony D’Angelo, Mickey Yerger; Third row: Billy Hemphill, Cliff Wallace, Earl Williams, Doug McGlaun, A.C. Chapman, Howard Hopwood and Bernard Levy; Fourth row: Tom Liegler, Bill Cunningham, Donald Brown, Glenn Walsh; Bill McCarthy, and Denzil Skinner. (Courtesy of Cliff Wallace)

When Denzil called him to come to New Orleans and consider the AGM position at the Superdome, Cliff had worked his way up to GM of Von Braun Civic Center in Huntsville, Ala., a city with a large board of directors and its own problems that Cliff was able to handle well.

Cliff flew to NOLA, talked with Denzil and toured the dome. On the way back to the airport, Denzil handed him a piece of paper on which was written: $55,000. It was 1980; it was enough.

Thus began a brief but powerful mentorship. “You gained a lot from him in a little bit of time,” Cliff said.

‘Denzil was a delegator. He trusted the people he picked. For example, he trusted Cliff to negotiate the contract for the Rolling Stones 1981 tour, which was promoted as their last. “I had to cut the deal with Louis Messina with Pace. Louis really ate my lunch. When I called Denzil after I cut the deal, I worried because I knew I had given Louis too good a deal.

“I called him late one night. He listened and after I told him what the deal was, there was this silence. I thought he’s getting ready to fire me.

“Then he said, ‘Cliff, I know that was tough. I might have done it a little bit different, but good job.’”

That was a classic example of nurturing a new employee, encouraging him to do better the next time, Cliff said.

“The next time he delegated a major decision was when I turned down Michael Jackson,” Cliff continued. The Jacksons were doing the Victory Tour with promoter and New England Patriots owner Chuck Sullivan and boxing impresario Don King. The scenario did not sit well with venue managers. The promoter was insisting on credit card sales only and advance purchases, like six months in advance.

“I was president of IAAM at the time. I took the position he was not going to take advantage of the people of New Orleans that I depended on day after day after day for every concert and create this huge monster and precedent that would effect everything we did in the future. I was scared having done that. Denzil said, ‘you’ve got to make the decision, weigh all the facts and make the decision.’”

Cliff was on CBS Morning News, and debated Bert Rose of Texas Stadium on Ted Koppel’s Nightline, all because he said no to Michael Jackson. “I was afraid Denzil might think I was a little too rambunctious, arrogant, out in front of myself,” Cliff recalled.

The whole time, Denzil wouldn’t criticize, he would coach. “He was a great coach. He would give you great advice and good support,” Cliff said.

That did come to an end…on the golf course. Denzil was in the habit of taking visiting sports jocks golfing. Since he was leaving New Orleans, he wanted Cliff to take up that mantel. Cliff did not golf.

No problem. He bought Cliff a beautiful set of clubs and a club membership. Cliff took lessons for a few months. Then Denzil organized a golf outing in Hawaii with Cliff and a few other buddies.

“When I had a flat tire on my golf cart on the 17th hole. Denzil walked over to me and said, ‘Cliff, I think this is probably an omen. Maybe you ought to hang this up.’”

“And I did. I haven’t played golf since. That’s one time he gave up on coaching.”

Denzil was a tough, tough negotiator, Cliff recalled. The thing he wanted at any point was to negotiate long and hard and get absolutely the best possible deal you could get for the company. Denzil’s negotiating skill was based not so much on the business but on the personality he was negotiating with. “Denzil had that great ability to switch. He was a thespian. He could change his outfit and become a different person. You have to play the part,” Cliff said.

Some wishes didn’t come true. He wanted to expand FMG internationally and came close to getting a management deal for the Hong Kong Convention Centre, where he did consult, as he did in London and Sydney. And he had an impact on the founding of Ticketmaster when he brought its founder’s product into the Superdome. Later, Hyatt invested and brought in Fred Rosen.

When FMG merged with Spectacor Management Inc., Denzil exited with a substantial founder’s fee of his own, continuing to consult, but mostly enjoying life and golf and family. He is survived by his wife of 71-plus years, Maxine, son David, seven grandchildren and seven great-grandchildren.

He is also survived by his greatest accomplishment as the godfather of multiple-venue private management. Denzil took risks and an entire industry benefitted. — Based on a true story as told to Linda Deckard.

I love that 1973 IAAM class photo. I can feel the youthful enthusiasm in each and every man (there apparently were no women in the industry then) who attended the school in hopes of meeting great success in the then nascent industry.

I noticed that, too. No women. Go figure.