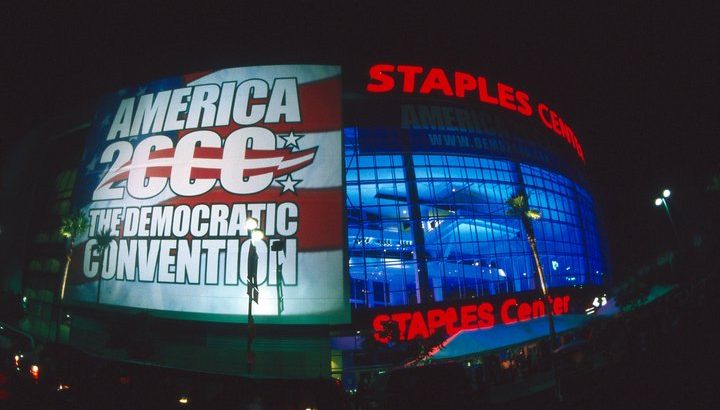

Lee Zeidman was calmly watching load-in of the Democratic National Convention (DNC) at Staples Center in Los Angeles in 2000.

He had this.

Staples Center had been open eight months. AEG, venue owners, sold their site to the DNC when it was a hole in the ground. It was built to handle two National Basketball Association teams, a National Hockey League team, a WNBA team, the Grammys and, oh sure, the DNC.

“We did the first ever Latin Grammys in August and, right after, the DNC came in,” Lee remembers.

There were about 60 suites for the big broadcast platforms.

“We were thinking, ‘we don’t know how the building really works right now. They’re building all that and I’m not stressing, because it’s all about the out. It’s never about the in. You can do whatever you want in the in, but it has to look the same on the out. Back then, there was nothing to change; we were still trying to figure it out, put it back the way it was because we’re only eight months open.”

Lee and staff were also cognizant of the fact they had to outshine Philadelphia, which had been “hotter than hell” for the Republican National Convention just held, a fact the RNC and media complained about…a lot.

“I went on record we’d be 68 degrees. This was the middle of July. And we were; we were cool.”

They put the media compound in an adjacent parking lot and ran enough power there to keep them humming…and cool.

“We had sized up everything for the building to have enough power to do the Grammys, the DNC, the NCAA; we had a enough power we wouldn’t need to supplement anything. So we were running enough power out there to power 6,000 family homes.”

It’s Friday and Monday the convention starts. Everyone is doing live interviews. Lee was being interviewed by CNN, Fox. The whole deal.

Friday night, he got the call from LADWP (Los Angeles Department of Water & Power).

To complete the picture, imagine Lee is staying at the Hotel Figueroa downtown for nine days during the DNC, because Staples Center is locked down. The first night at the pre-renovation Hotel Fig, there’s a belly dancer convention. Between that revelry and the noisy window box AC unit, he’s getting no sleep. He’s beat. He takes the call.

DWP: “Can we meet with you?”

“Sure, come on down.”

“I believe we have a power issue.”

“What do you mean we have a power issue?”

“Well, we just put Disney Hall on line, finishing up construction, and we powered it up and all the fuses blew. We believe you have the same fuses, on our side of the vault, not your side.”

Lee knew everything on Staples Center’s side of the vault was even over-sized. AEG had paid for all this extra capacity. He just didn’t know what he didn’t know.

So LADWP needed to check it and then pow wow.

“There is a problem. Here’s what we’re recommending: that you don’t run the AC 24/7; you shut off the freeway marquees; you tell the DNC that they need to cut back on theatrical lighting or don’t use any at all on the stage; cut back all concessions uses; and, then, go to the media compound, power them all down, bring in four large generators and then power them back up.”

“Are you fucking kidding me? If I go out there and tell the media, after they’re in there 20 some days, that you have to power down and we’re bringing in generators—what story is getting out there? That L.A. and Staples Center don’t have enough power for the convention they got.”

Backed into a corner he hated, Lee went to the DNC committee and had to tell them what DWP was recommending. Predictably, they said no, there have to be other options.

Saturday dawns and the DWP is trying to compromise. The changes are down to cutting the marquees; running some air; cutting way back on theatrical lighting and, still, powering down the media compound.

“There’s no way I can do this.”

Saturday night, DWP is trying to figure out how to reroute cables coming into Staples Center from other areas, to draw power from other parts of the city.

“What’s the exposure? What could potentially happen?”

“You could lose all power and you wouldn’t get it back.”

Lee imagined President Clinton is making a speech or VP Al Gore is accepting and the arena goes dark. Unacceptable.

Sunday morning Lee is in AEG CEO Tim Leiweke’s office saying “get Mayor Riordan on the phone right now. I’m not going down for this. If we lose power, not only will our jobs be done, there will never be a big event that comes to Staples Center from now on.”

Sunday, DWP comes back.

“Here’s the real problem. We know you did everything you needed to do to have the right amount of power coming into your building. We never thought you’d ever need more power than what you ever used at the Forum so we sized it based on what you had at the Forum.”

Unbelievable, but true. The Forum is 330,000 sq. ft. You can fit 2 and 1/2 Forums in Staples Center, which clocks in at 1 million sq. ft.

“Are you kidding me? What will we do?”

“We have these better fuses we think will hold. We’ll divert another line in. If one goes down, we can cut over very quickly. But we want you to move some power around in the building. Take some load off the various areas. We won’t power down the media compound, we won’t mess with the theatrical lights and we won’t cut into the air conditioning. You do that and we bring in this other line, we think we can get by.”

Every hour that day, Lee is in the vault checking power ampages.

“I can’t believe I’m doing this; I can’t believe this is happening; I can’t believe I’m in this position eight months after the building opens. And I’m listening to the belly dancers and the air conditioning going rahr, rahr, rahr. I can’t sleep. I’m stressing every night. Four days…four days,” Lee moans.

It’s epic venue manager angst. Throughout the DNC convention, Lee is rolling thoughts through his mind. “Are we all right? Are we all right? I think we’re all right.”

As history knows, they were all right. The power held, the convention was great. Finally relaxed, Lee was looking forward to that best of venue manager perks, meeting the talent. He was scheduled for a meet and greet with President Clinton that final night.

Then he gets another call. This time it’s the Security Command Center. The FBI, Secret Service, Department of Homeland Security and LAPD, they’re all there. They had set up a free protest zone, as they do at all these conventions, at L.A. Live across the street from the arena. There was a big K-rail and fencing to protect everyone coming into the convention zone from the protestors. Rage Against the Machine was playing for the crowds. And the protesters went crazy. There were smoke bombs, people trying to scale the fence, trouble no one wanted to see.

“We want you to lock the doors and keep everyone in once the convention is over.”

“We have 25,000 people here; we’re in a safe zone. Why do I have to do that?”

“They’re going to jump the fence.”

“Well, I have 186 glass doors here. If they get over the fence what’s to stop them?”

“If they get over the fence, we’re not shooting rubber bullets.”

“Okay, I get it.”

So Lee and staff delayed everyone in the building and held the buses they were departing in while security and LAPD got everything under control. They never did breach the fence.

“I never got to meet Clinton.”

The rest of the story: After the DNC, LADWP came back and ripped out all the cable and put the right sized equipment in place, complete with an automatic transfer switch. “If one of our two lines went down, the other would automatically kick in,” Lee said.

Among the many souvenirs in most arena GM offices — press photos, meet and greets, posters and awards — Lee has a most unique item: a three-inch section of the cable preserved on a plaque with day and date, the cable that could have brought disaster to the DNC. — Based on a true story as told to Linda Deckard