Only a few venue managers have been challenged to operate a company that doesn’t exist for a building that hasn’t been built.

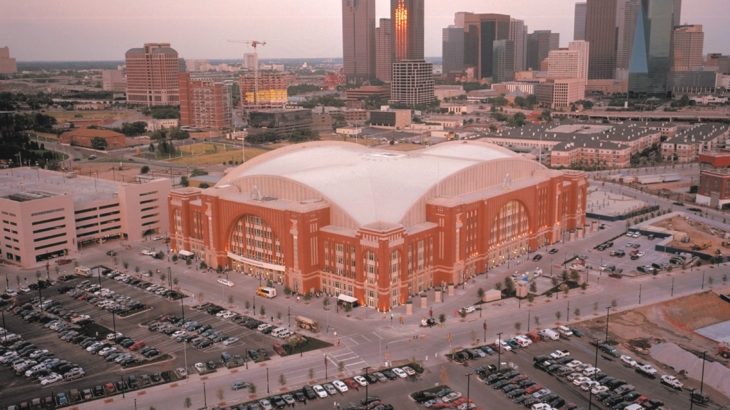

When Brad Mayne arrived in Dallas to create a company to build a new $412-million arena for hockey’s Stars and basketball’s Mavericks, a strong business acumen and an appreciation of good lawyers that saved the day.

It was April 1998 and the two teams had obtained the city’s buy-in to build an arena both organizations could use. The city did not want to be negotiating with each team, insisting instead that the team owners create an entity to enter into an agreement for development of the venue.

“So they needed a CEO to come in and create the company,” Brad recalls. “It was before the building had been designed. My first week on the job was choosing who the architect would be.”

He tapped into a long career in venue management as he moved into newly-established offices overlooking the 72-acre site for the arena and Victory Park with Jack Hill of Hillwood, the development company, as officemate.

Those early conversations with team owners are etched in Brad’s memory:

“How are we going to set this company up?”

“Go ahead and get it incorporated.”

So they assigned an attorney for Brad to use. As the two were working through that, it was time to ask:

“Okay guys, we are going to need money to operate.”

“We thought you’d be able to generate the revenue.”

“We don’t have an arena right now.”

“One of the options we do have is managing Reunion Arena. Do you want to do that?”

“Yes, we want to do that if we can get the right management deal.”

“Then you need to put that together.”

As he’s “putting everything together,” the need for a liquor license enters the mix. The only way to get a liquor license is if the owners of the company give their personal information, their social security numbers, etc.

“When I made that request to Tom Hicks (Mavericks) and Ross Perot Jr. (Stars) they said, ‘We’re not doing that,’” Brad remembers.

So Brad and the lawyer created a limited liability partnership, enabling the CEO of that organization to get the liquor license. Brad added his social security number to the ask.

“You end up with the liability. You are an individual named in the legal action. So you need protection. You have insurance that covers the business and the officers of that business. And you usually set up different entities within that organization and each has different responsibilities – tax, business, operations, equity. It takes attorneys who have done that kind of work before. I’m at their beck and call at how they set it up and how it is best operated. Whoever is the entity receiving the benefits can protect some of the assets, depending on what the legal action is.”

“That was my first time being a CEO. The good news is we had really good attorneys.”

Brad became CEO of Center Operating Company, the entity formed by the owners of the Mavericks (5 people) and the Stars (11). But it’s not that simple. Eight people from the Stars had ownership in COC and four from the Mavericks, so it was not common ownership.

“When we needed the private note for the money to build American Airlines Center, we did contractually obligated income instead of collateral. You offer up the revenue streams you have. We set it up that the revenue generated by suite sales, club seat sales and sponsorship sales was the contractually obligated income.”

The set up had waterfall accounts (all the obligations plus operating funds), and money would flow into each account until full, then flow down, until it reached the bottom. The lowest account was money that individuals who owned the company could take out and that would be the return on their investment. Some of those waterfall accounts were for requirements fora certain number of years to operate the entity – to protect the lenders so if the entity went away, the lenders would have a period of time where they would have enough money to operate the entity until they decided if they would sell it or hire someone to manage it, etc.

“So we had all these different accounts that had to be filled before there could be any equity pulled from the revenues.”

That’s all good on paper, but it took months to negotiate a deal to operate Reunion Arena. In the meantime, Brad needed to choose an architect, CFO, operator, clerical staff, and “an HR person, if we’re taking over management.”

Brad went back to the teams for operating cash. Fortunately, “we came to the conclusion the Stars and Mavs had to cover us until we could start generating revenue.” The Stars took on payroll and the Mavs covered operating expenses, for instance. His charge was to pay that money back when Reunion Arena started generating revenue for COC.

Meanwhile, his group was also able to put together the construction loan that allowed COC to use monies to put out the request for proposals and to hire architects to do the design and development of American Airlines Center.

Center Operating Company took over Reunion Arena in October, more than six challenging months after Brad Mayne arrived in Dallas, charged with finding his own cash flow.

And that’s why a business degree serves venue managers so well. It’s not all about music and sports. — Based on a true story as told to Linda Deckard

(Editor’s Note: This is the first of several installments about Brad’s early days at American Airlines Center, including what he learned from Mark Cuban and the wonder of working closely with billionaires.)