Experience comes by doing. Expertise follows. In Maureen Andersen’s case, the two were almost simultaneous.

“You settle the show. You’re ready.”

Those were the instructions that threw Andersen into the thick of things at a young and still inexperienced age at the Denver Center for the Performing Arts.

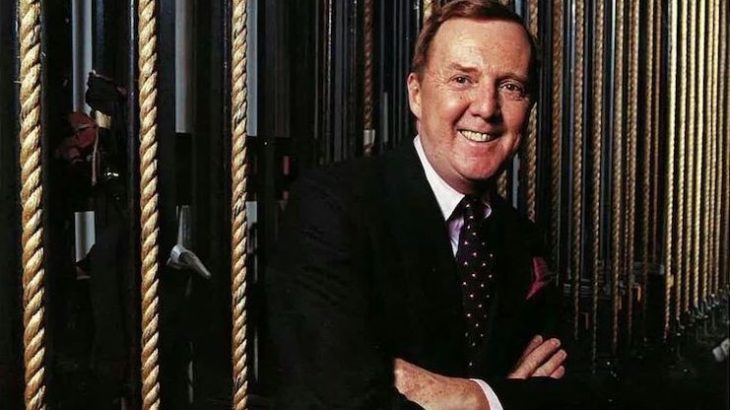

Robert Garner, Garner Attractions and later Center Attractions, produced Denver Center’s Broadway Series. He’d been a scientist by trade, then a banker and then someone said, “We need help with this Broadway event,” and he bankrolled it with $10,000. He eventually became the guy who did Broadway in Denver.

He was an impresario and he booked things on a handshake, Andersen recalled. “Your word meant everything and because he had a reputation, Denver, which wasn’t a first-tier city, more like one of the bottom two or three, was getting shows that were routing across the country.”

In 1986, Garner had booked “Tango Argentino,” a summer show.

“Bob didn’t want to settle the show. He didn’t want to come back downtown and write the check and send them on their way. He’d worked hard enough that week. So he said, ‘You’re going to do it,’” Andersen remembers vividly.

“I don’t know how to do it.”

“Yeah, you do.”

He pointed to the file cabinet.

“Everything you need to know is over there. Just look at the files.”

And he handed her the contract.

Never having done it before it was intimidating to Andersen. She found that it is amazing what you can learn by going into a file cabinet and following repeatable behavior. Road show agreements are remarkably consistent. Here is what the bills look like, the ad slips and the advertising bills. You need a copy of the ad attached to the bill. And the gross adjusted box office receipts. “That language is still used today, just like it was 30 years ago. Certain allowable expenses are still the same,” she said.

Thursday, Garner came in and said:

“Have you looked at the contract and the files?”

“Yes, I have.”

“Here are the ad slips and invoices for the ads, the piano tuner bill, the oxygen bill, the loader’s bill and the dresser’s bill.”

In Denver, you have to have oxygen backstage, because of the altitude. Imagine you come from San Francisco, which is sea level to a mile-high city. Your first few days, you’re huffing and puffing no matter how good a shape you’re in. “We had to have oxygen on both sides of the stage so performers could come off and breathe a bit of oxygen. The same thing happens at a Broncos [football] game,” Andersen said.

Garner handed Andersen this whole stack of bills and a contract. She had done the research, delving deep into the file cabinets for similar weeklong shows, like to like. She had researched the deal split, though she admits “I didn’t know what it meant except in vague terms. I studied contracts and settlements for a week.”

It’s curtain Sunday night. The matinee had gone well, no issues, and the box office manager came down with the final settlement. Then the company manager, Hans Hortig, called and said there was a problem with the contract.

“It’s not quite right. You owe me a different percentage than this.”

“No, that’s what my contract says.”

“I don’t care what your contract says, my contract says this.”

They ended up at a stand-off. Andersen kept calling Garner at home — “You need to help me; you need to tell me.”

Garner simply stopped answering the phone, after he’d hung up on her.

“It was one of those moments; somebody was going to have to turn bluer and Hans was holding the show. We were five minutes after curtain,” Andersen remembers.

“Okay, we’re going to have to figure this out later; let the curtain go up.”

Bottom line, she had turned blue.

About 8:30, Hortig came down to her office, told her visitor to leave, reached out his hand and shoved everything off her desk. He sat down in front of her and said:

“Okay, are you ready to learn this now?”

And he went through it piece-by-piece, item-by-item, contract-to-contract, bill-to-bill, settlement-to-settlement.

“He taught me exactly what I needed to do and what all the terms meant. We did it together,” Andersen said.

She wrote the check for what was owed. In those days, whoever was settling had a hand-signed check, a blank check, and all the responsibility that goes with that.

“I wrote out the check, reached out my hand to shake his and he gave me a great big hug and said, ‘You’re ready.’”

“I sat down and cried.”

“The next morning Bob came in and picked up his copy of the settlement and all the statements and box office reports. Then he looked at me very smugly and said, ‘You learned it, didn’t you?’”

“From that day on I knew how to do a settlement and was no longer in fear. I learned there was nothing that couldn’t be reconciled and, if you had to, you could sign under protest and let the New York office handle it later. This time, we were fine. It was a business deal but, in live show business, things happen. There is always a way around it. Someone took the time to teach me.”

She found out later that Hortig and Garner cooked the whole scheme up. Garner gave her the first signed contract, but Hortig had the second one with an addendum to it. It was supposed to be a 70/30 split after expenses, because Garner had negotiated higher expenses. Andersen had a contract, signed by Garner, that said it was 60/40 after expenses.

“We had to get to that 30 percent and he said curtains not going up until we settle this,” she remembered

“Bob did it on purpose to see how I would handle it. He wanted someone who would be a second to him so he didn’t have to come back and do settlements. He was the perfect mentor. He didn’t coddle you. He challenged you.”

“He taught me all the greatest things about show business that I still love and still believe.” — Based on a true story as told to Linda Deckard

PHOTO: Robert Garner, Center Attractions, backstage at Denver Theater. Courtesy of Maureen Andersen.

What a great story! Thank you for sharing this.