Remember the day you had options when the headliner couldn’t perform? There were ways to save the day for the entrepreneurial risktakers in the concert business. Experience helped tip the scale.

Mike McGee had an experience in Lakeland, Florida, in October 1975, that turned out quite differently than originally planned.

It was the first time the Lakeland Civic Center scored a double play, two shows over two nights. The bill was Rod Stewart with Aerosmith and Jeff Beck and a coffee house guy named Bryan Bowers.

“We were going to do a Wednesday/Thursday. We went on sale. But there were a bunch of complications with Rod Stewart. He supposedly was ill. His manager, Billy Gaff, called us at 2 p.m. the night of the Wednesday show and said Stewart wasn’t going to play that night.”

This show was a big deal for Lakeland. It was sold out both nights, 10,000 seats per. They moved the Wednesday show to Friday and got the word out. All you had to do back then was go to the radio. Everything was viral, but in a different way. People were offered the chance to get a refund or use the Wednesday ticket Friday.

First thing on Thursday, and throughout the day, right up to the time they were going to open the doors, McGee started checking on Rod. “How is Rod feeling?”

Finally, it was time to open the building and let the people in. One final check with Gaff. It’s all good. They open up, with near capacity people in the building, for a 7 p.m. curtain.

At 6:45, Gaff calls.

“Rod’s thought it over. He’s not going to play tonight.”

What were they going to do? McGee and staff quickly made some decisions:

• Play a show that night because Jeff Beck and Aerosmith was a good show in and of itself.

• No partial refunds. If people wanted a refund for the show that had been advertised, they got a 100 percent refund and they were welcome to leave the building.

• Make an agreement with Billy Gaff that Rod wouldn’t play Friday if he didn’t play on Thursday. “We decided to play the ‘new’ show Friday and see if we could salvage the thing.”

At 7 p.m., McGee went on stage to tell the audience what would happen, unsure what the reaction would be. “It’s one of those plays when you don’t know if the building will be torn apart.”

“Ladies and Gentlemen, There’s been a change in tonight’s performance. Rod Stewart will not be performing tonight due to medical reasons. I just spoke with his manager and he’s unable to perform.

“We’re going to go forward with the show. We think we have a great lineup for you. We talked to the bands and they said they would go all out to make it a great night for you.

“You’re welcome to get a refund if you like. There are no partial refunds. If you are going to get a refund, they’re available at the ticket window until 9 p.m.”

That deadline was for torn tickets only. Whole tickets could be refunded later.

“For the most part, everyone was happy. Lakeland drew from a 100-mile area, so by the time someone had driven from Daytona Beach to Lakeland to see a show, they wanted to see a show,” McGee recalled.

“We refunded maybe 12 percent of the tickets. The next night was a complete debacle, but that’s another issue.”

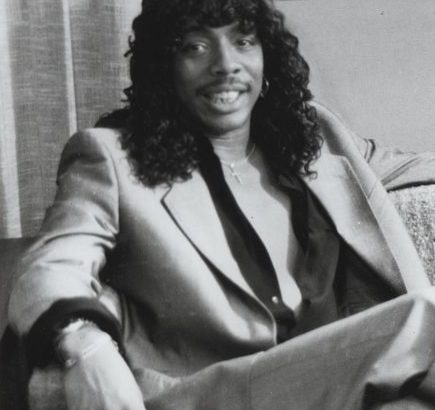

Fast forward to Texas, August 1982, when McGee managed the Houston Summit. Al Haymon was promoting Rick James with Cameo, Ray Parker Jr. and a couple of other strong acts on the show. Packaging was hot.

“I get a call at 11 p.m. the night before the show from Al saying, ‘Rick James collapsed on stage tonight. He’s in the hospital and he’s not going to be able to perform tomorrow night. What are we going to do?’”

McGee replied by telling him the Rod Stewart story, and then said:

“I think everyone is ready for a show tomorrow night. They’ve already bought their tickets and have plans to get their nails and hair done, and do all that goes along with it. They’re excited about it, and I think we have a great show.”

This was when Ray Parker Jr. had “Ghostbusters” out and Cameo was huge, too, with a couple of hit songs out.

“What we need to do is maintain credibility. I want you to meet me tomorrow morning at Hobby Airport at 7 o’clock and you and I are going to the radio stations and tell them what happened. We’ll tell people that Rick James collapsed on stage last night and he’s unable to perform tonight. However, given that set of circumstances, we are still going to have a show. If you want a refund, we’ll give you a 100 percent refund. But once the show is in process, if you you are in the building, we will not give refunds after 9 p.m.”

“Al was nervous because he had a bunch of money on the street. He was a relatively new and young promoter at that time and couldn’t afford to take a really big hit.”

So that morning, McGee met Al at the airport and they went to the radio stations, explained the situation and talked up the show and got the DJ’s to talk it up. That night, they positioned people at the doors. Before each ticket was torn, fans were told the circumstances. If they came in, they were in and they still had a chance to get a refund till 9 p.m. If they didn’t get a refund, that’s what the show was going to cost.

“It’s going to break me,” Al worried.

“Al, I guarantee you we won’t give back more than 15 percent of what’s been sold.”

They wound up giving back 11 percent.

“I think for the most part everyone was happy. It made Al a big believer in me. That wound up being a friendship that is still there.”

LESSONS LEARNED: Sometimes you have to think on your feet and find a way to come to a positive outcome. For Rod Stewart, the promoters were Jack Boyle and Cecil Corbett. “They were the ones we were talking to and they were like, ‘Can we do that (logistically)?”

“We’ll make it happen. You just have to trust me.”

They brought a tremendous amount of business to Lakeland after that.

With Al Haymon, they learned if you are candid, up front and honest with the public, and explain the circumstances and the situation, they’ll be tolerant. But don’t let them find out after the fact and don’t let them find out in the middle of something. Then you’ll be in a situation where things will get out of control and you’ll have problems.

Back in the day, McGee rented the building for a flat fee against a percentage of the gross. “We technically were a partner of the promoter or entity putting on the event. It was our obligation as facility operators to enhance everything possible and conceivable to make their show do well. If we got 10 cents on the dollar, if the show goes to $100,000, we got $10,000, but if it did $200,000, we got $20,000. We made more money by helping the show.”

That created a dynamic within the company, which became Leisure Management International and ran dozens of venues, that the harder they worked in behalf of the customers to bring events to the building, the better things would be for everyone.

“You have to go through and experience that a little bit.” — Based on a true story as told to Linda Deckard